What does it take to rescue animals in Africa’s roughest regions? Meet the wildlife veterinarian whose new photography book lifts the veil on the joys and challenges of conservation. By Nell Hofmeyr

Dr Michael Kock is a wildlife veterinarian with a keen eye for photography. For 39 years he worked exclusively with wildlife in protected areas, looking after a variety of tusked, horned and toothed beasts in some of Africa’s most storied parks, like Hwange and Niassa National Reserve. His trusty Nikon accompanied him on every expedition, from the scenic shores of Africa’s east coast to remotest Cameroon, always within reach in case a photo opportunity revealed itself.

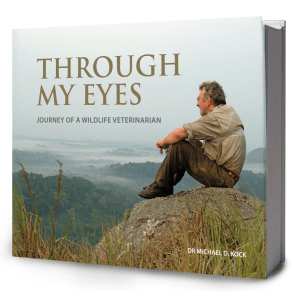

In 2017, he decided to create a visual record of his life’s work drawn from thousands of images taken in the field. Through My Eyes: Journey of a Wildlife Veterinarian is a striking account of a life lived in service of wildlife and people in a conservation context, filled with tales that could rival those of the most intrepid explorers.

“It’s a record of my life history but also has a very strong message in terms of the challenges related to conservation, travelling and photography,” he explains. “It’s about what it takes for conservation to be sustainable and successful down the road.”

Wild encounters

Being a wildlife veterinarian is demanding and carries obvious risks. Wild animals are territorial, unpredictable, dangerous, wary of humans, and now, thanks to poaching, more elusive than ever.

“Some animals have changed their patterns of behaviour to avoid being poached. Forest elephants are a fairly classic example of this. Historically, you would find them in forest clearings, often during the day from early morning. Now, they only come in around midnight and leave before first light.

“They seek out the thickest vegetation possible in the most horrible hilly country and spend the day there, which makes it hard to track them. In their eyes, I’m no different to poachers. There were times where I’d be five metres from a female and it was impossible to see what was going on. I couldn’t determine her size or if there was a small calf with her. We always avoid immobilising a cow if her calf is nearby because it’s too risky. If she charged me, I’d be history.”

From forest thicket to open Savannah, the book reflects the challenges of being a vet in harsh, remote environments where resources are scarce.

“Working in places like South Sudan, Congo, Cameroon and Gabon is some of the toughest stuff I’ve done. You don’t always have a lot of support in these countries, so you’ve got to have your wits about you when dealing with people, bureaucracies and wildlife. The animals can be dangerous and difficult to work with but as a veterinarian, I have a responsibility to take care of them. It’s my job to keep them alive.”

Also read: On the road with travelling conservationists

Conservation: an uphill battle

Having worked on three continents and in 14 African countries over the span of his career, Michael was able to capture how the conservation picture changes between countries.

“South Africa has a very strong conservation ethic within national parks. When you go to other countries, however, the challenges are acute. They mostly revolve around governance, corruption, poverty, capacity and people pressure.

“In all of the African countries I visited, I had to deal with conflict, civil war or major issues related to poaching and illegal bush meat harvesting. There are some places, like Cameroon and Gabon, where it’s just tragic. Most national parks are chronically underfunded and staff morale is an issue.”

While the threats to wildlife and landscapes are severe, there is action being taken. Asked about which NGOs and projects give him hope, Michael says: “African Parks (AP) is doing some remarkable work. Take Akagera National Park in Rwanda, for example. They have completely turned around since AP assumed co-management. And despite the chronic problems in Zimbabwe, there is a small group of people in the private sector partnering with parks to create change.”

He singles out Gona-re-Zhou National Park (GNRZ) in the south-east corner of Zimbabwe’s lowveld as a prime example. “I go there every year to participate in a training course on wild animal capture, held at Malilangwe Wildlife Estate next to GNRZ – it’s actually featured in the Zimbabwe chapter of my book – and I’ve watched the park transform completely under professional co-management through the GNRZ Conservation Trust.

“They’re even thinking of reintroducing black rhino now. So, there are success stories, but they’re often islands surrounded by a mess of stressed landscapes, too many people and illegal activities.”

The lure of Africa

Through my Eyes is as much about travel as it is about conservation. What is it about Africa that keeps Michael enthralled?

“The appeal of Africa is that it’s still so raw in places but very modern in others; it’s a continent of stark contrasts. Plus, it’s incredibly beautiful and the diversity is extraordinary, just look at the Cape Floral Kingdom where I live. I sometimes wish I could be reborn in Africa 500 years ago. Just imagine South Africa when there used to be springbok migrating in their millions across the Karoo, elephants wandered through the Cape and rhinos existed throughout the continent.”

In true overlanding spirit, he has a taste for the more rugged destinations.

“One country that just absolutely fascinates me is Ethiopia. It’s the most extraordinary mixture of history and culture, and it has more livestock than any other country I’ve been to in Africa. From the Simien mountains to the Danakil Depression, it’s just a mix of colour and diversity – a photographer’s paradise.”

Also read: Ten reasons to visit Ethiopia

As for the subjects he returns to time and time again?

“People. People and their activities, where they live, what they do, their culture, the clothes they wear, their livelihoods, their interactions with animals both domestic and wild, the illegal activities, and so on. In Africa, people are extraordinary subjects in their variety and diversity. In the conservation world, we ignore them and their hopes and dreams at our peril!”

About the book

Through my Eyes: Journey of a Wildlife Veterinarian is a coffee table book featuring 1,400 colour photographs over 600 pages. Driven by the mantra “a picture is worth a thousand words”, it is a visual retelling of Dr Michael Kock’s professional journey. While deeply personal, it tells a bigger story about the challenges facing conservation and biodiversity in Africa and globally. The book (R980) is available in our online shop.