Travelling north from Cape Town, Steinkopf is the last village on the N7 before reaching the Namibian border at Vioolsdrift. Normally travellers are in a hurry to get to Namibia and don’t pay any attention to this small and apparently rather insignificant town in the Northern Cape. Lizette Swart spent some time on a recent overland trip and discovered that it has a fascinating history…

Town history

“I learnt that the village developed when a group of Nama settled at a fountain approximately 5km south of the current town and called it Tarrakois or Bezondermijd, which means “peculiar girl”. When reverend Heinrich Schmelen of the London Missionary Society arrived in 1818, he renamed it to Steinkopf, after Dr. Karl Steinkopf who donated a large sum of money towards the development of a mission station.

The people gradually moved north and settled at what they called Goegaas, where there was plenty of water in the form of a permanent spring. In 1821 the mission station was moved to Goegaas and the settlement became known as “Kookfontein” (boiling spring). The Rhenish Mission Society took over this station in 1840 and Reverend Ferdinand Brecher built a new church and school, and also restored the name to Steinkopf.

Today the town provides services to the local stock farmers and many of the inhabitants work on the Namaqualand mines.”

Lizette was guided by Letitia Louw, who has run the Steinkopf Tourist Information Centre for more than 15 years. She recalls: “We wanted to visit some rock paintings on a nearby farm but unfortunately the farmer wasn’t there. So, instead we headed north out of town for the Kinderlê Monument.

Kinderlê Monument

A Nama descendent, Ouma Vigiland, told Letitia the history of the monument: the Nama clan under Abraham Vigiland stayed in this region during the 1800’s. Two of his San farm hands slaughtered a horse without his permission and Abraham punished them with the whip. The next Sunday, while the adults were attending a church service in Bezondermijd, the workers decided to take revenge and killed the 32 children that were left at the Nama camp. The children were buried in a mass grave which was marked with a stone, and on 28 June 2003 the site was declared a heritage site.

Vigiland Farm

For the next stop we picked up Oom Johannes in Steinkopf and set out to a nearby farm that belongs to Ouma Vigiland, grand-daughter of Abraham Vigiland, who wasn’t at home. We left my Terios parked in the shade with a cat, a few chickens and two rather large pigs as company, and followed Oom Johannes into the veld. He pointed out the open-air church used by the Vigiland family, as well as the graveyard and an old “kookskerm” (cooking shelter) made from dead “melkbos” (Damara milk-bush or Euphorbia damarana).

Back at Ouma Vigiland’s house (a very hot and thirsty 45 minutes later) I stopped at a tap when I was unexpectedly charged by the pigs who were at our arrival lazily loitering in the shade. I followed the first rule of the bush: whatever you do, don’t run! It usually works with wildlife and thankfully it also worked with the pigs as they were in fact aiming for the water and not me.

It was when the cat came meowing at my feet that I realised that there was no water available for the animals. The tap ran dry just then, but Oom Johannes found the pump and soon we had fresh clean water gushing into the trough. After drinking herself full the sow sauntered back to the shade, but the boar had other plans. Soon he was inside the trough, enjoying the water Letitia splashed on him.

Next he rolled in the mud, but when he decided to use the Terios’s bumper as a scratching pole, I decided it was time to leave.

Van Wyk Monument

Letitia then took us to the Van Wyk Monument which honours Cornelis and Elisabeth van Wijk (neé Van Den Heefer), the first Van Wyk’s in the area and ancestors of the current farm owners.

Departing from the monument, I was keen to continue on what Letitia and Oom Johannes called “Die Meelpad” (the flour road), which is the route the old postal coach followed from Port Nolloth to Steinkopf. Letitia was a bit uncomfortable as the road was, according to her, very bad and only wide enough for one vehicle at a time. It would be impossible to turn around if we had a problem, but as I managed to convince her that I was an expert off-road “reverser”, we set off down the hill into the valley below.

As promised the track was narrow in places, with a few dongas (wash aways) here and there. I noticed Letitia and Oom Johannes quietly shifting their weight to my side of the vehicle when the drop on the left became steep, but we were travelling downhill and the Terios made light work of our descent. Uphill in the rainy season might have been a lot more interesting…

Halfway down my attention was drawn to a small herd of donkeys, and Letitia told me these were wild donkeys that live from the land, similar to Namibia’s famous wild horses.

At the bottom of the descent the path turned sandy and I now understood why it is called the “Meelpad”. Apart from a narrow escape in a particularly loose sandy patch, we easily crossed the valley until we joined the Old Anenous Pass. The name Anenous comes from the Khoi nani/nus, which means ‘side of the mountain’, referring to the steep cliffs. The new, tarred Anenous Pass was completed in 1979 and runs above the old pass.

The old pass runs parallel to the narrow-gauge railway line built by the Cape Copper Company in the 1870’s, and the original stone buttresses for the viaduct can still be seen next to the road. Oom Johannes pointed out the openings where the supports for the rails were mounted.

Klipfontein

Next we headed to the old Klipfontein Railway Station. It was the overnight stop for the old narrow-gauge railway that transported copper ore from the mining villages of Okiep and Nababeep via Steinkopf to the harbour of Port Nolloth.

The lack of water along the route meant that steam locomotives could not be used. Instead, a team of four mules hauled each of the ten ore wagons. It took 40 mules to pull one train, and the 146km journey took two days to complete with an overnight stop at Klipfontein Hotel at the top of the Anenous Pass. Fresh mule teams were stationed along the line as the Cape Copper Company owned 220 mules, 18 donkeys and 23 horses as well as a dedicated tannery which produced harnesses for the animals.

In 1886 the first steam locomotive was used on the Port Nolloth section of the line, but a steam-hauled train covered the entire distance for the first time only in 1893. On the westward journey, the train ran without traction down Anenous Pass and covered the entire 88km to Port Nolloth powered by gravity alone.

During times of drought mules were still used and the line remained in use until 1942, when it was diverted to Bitterfontein. The track was lifted in 1942 and all that remains today is the occasional raised sand and gravel ridge seen at Klipfontein next to the N7 between Okiep and Steinkopf, on which the railway was built.

At Klipfontein one can still see the old platform and water tower used to fill the steam locomotive, as well as the ruins of the old Klipfontein Hotel.

Across the road we visited the graves of British Soldiers who died in the Anglo-Boer War between 1899 and 1902.

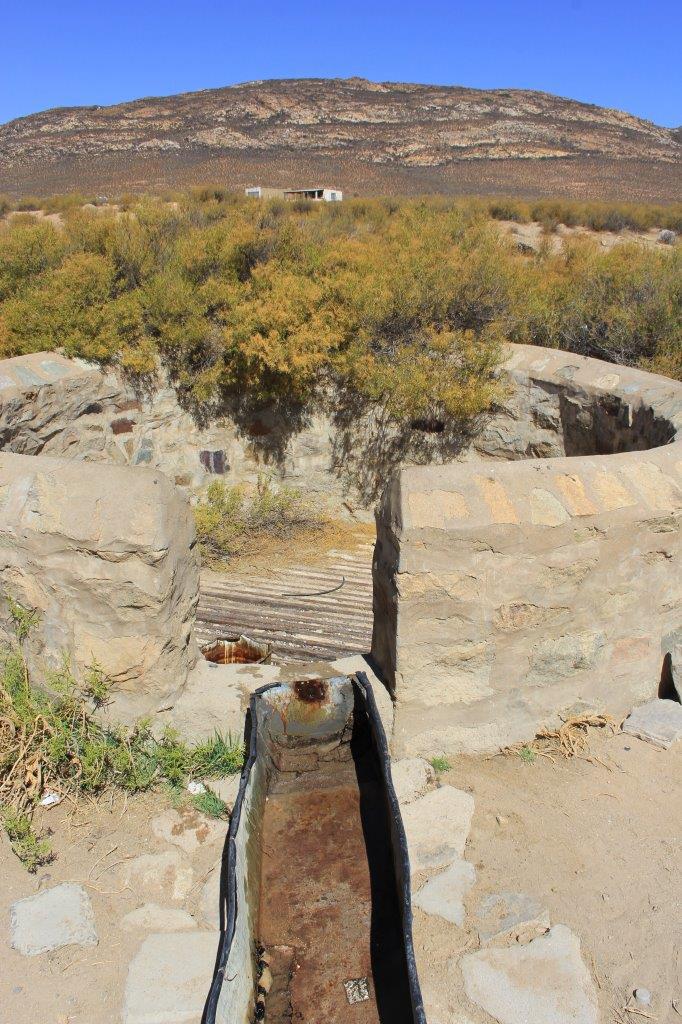

Heading back towards tar, Oom Johannes insisted that we stop at an old well covered by pieces of the old railway line. An opening was left to lower a bucket into the well. By then we had worked up quite a thirst and filled our water bottles with fresh, clean, cool water from the well. They should bottle the stuff!

Steinkopf Cemetery

Back in Steinkopf Oom Johannes directed us to the public cemetery to see the graves of the Brecher family, who are off-spring of Reverend Ferdinand Brecher, who built the Rhenish Mission Station and school in 1840.

The Ferdinand Brecher Primary School as well as the main road into Steinkopf, Brecher Street, pays tribute to the Reverend.

Rhenish Mission Station

Our final stop was the old Rhenish Mission Station, situated on the grounds of the Dutch Reformed Church. Today the building is used for school and church functions.”

Next time you visit that area, don’t just drive past Steinkopf. Contact Letitia at the Information Centre and arrange to have a fascinating guided tour. Kookfontein Rondawels offer comfortable self-catering accommodation as well as camping.

The San killed the Nama-children, and Abraham Vigiland and his followers did take revenge, yes.

I am not 100% sure about Gnl. Christiaan de Wet’s involvement around this area, but a lot of the action around Kimberley and Bloemfontein took place under him.

There is a fort in Augrabies National Park (not possible to access it) and remains of a fort in Springbok, that was occupied by Manie Maritz.

Very nice story of the history and remains indeed. As if I walked/rode along with the others!

Thank you Arnold, it was a fascinating day!

Interesting history indeed.Did those killer-Nama’s got punished?

I just finished a book about the Boer War which mentioned pretty Boer successes (with their leader De Wet if I remember well) in that area.

Apparently a group of San attacked at night cutting their throats. Their tracks were later followed and they were cornered near the Orange River where many of them were shot and killed