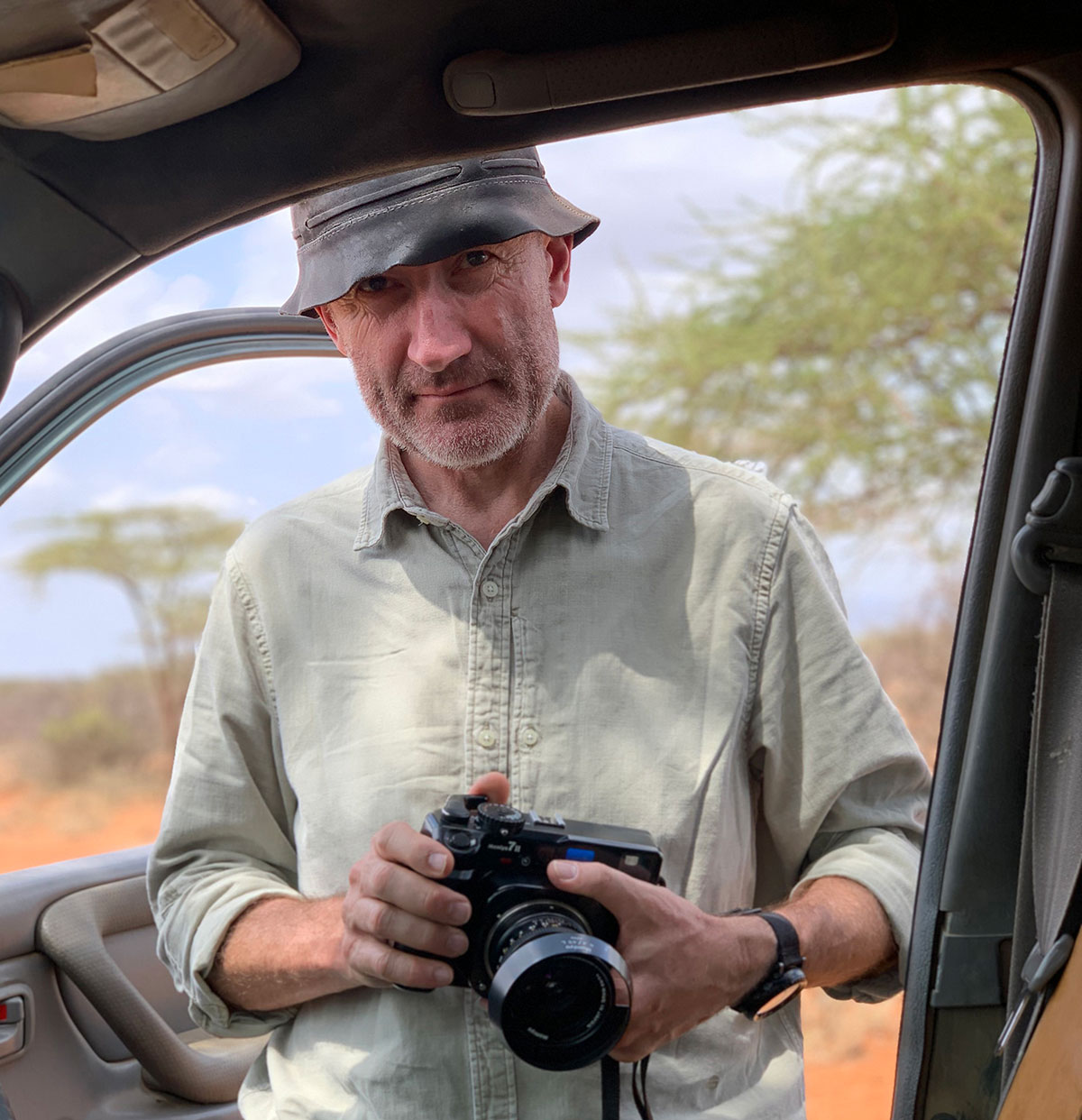

Photographer David Chancellor travels to the remote corners of Africa for his work. He talks to us about finding his way and the power of nature. By Magriet Kruger

David Chancellor is telling me how an elephant charged him. “I was photographing these elephants last week and I’d spent quite some time with them, but I’d gone away to check on something. When I returned, I must’ve startled one, because he charged towards me… But at the sound of my voice, what was a mock charge turned into a run. Soon the baby elephant was sucking on my trousers.”

Close encounters with elephants, days spent deep in the bush and trips to far-flung places – this is the stuff of daily life for the British-born photographer. Reteti Elephant Sanctuary in Kenya’s Namunyak Wildlife Conservancy is typical of the locations where Cape Town-based David does his work. Places like the Omo Valley and the Simien Mountains – destinations well off the tourist track.

For David, the journey tends to begin where the road ends, whether he’s working with anti-poaching teams in the field or recording the ways of the Samburu people. It’s this commitment to finding the story – and finding fresh takes on the world – that has earned him widespread recognition. Over the years his documentary reportage has won multiple prizes, from the World Press Photo Award to the Wildlife Photographer of the Year.

Where people and wildlife collide

When I catch up with David, he’s in northern Kenya on assignment for National Geographic to investigate the effects of Covid-19 on community-based conservation projects. What happens when there’s no tourism? What value do people place on wildlife then?

It was while criss-crossing South Africa by road in 2002 that he found himself drawn to the theme of wildlife as commodity. “I was spending an enormous amount of time driving along game fences in the Eastern and Northern Cape. When I visited these game farms, I became intrigued that they knew exactly how many animals they had. I had naively thought that Africa was open land, that animals weren’t fenced in. Once I realised that was the case, I wanted to delve into how and why we manage wildlife.”

Since then David has travelled to the back of beyond to tell the story of how people relate to wildlife – as hunters, guardians and admirers. I’m interested to know how he uses T4A maps on these trips through remote areas.

“Tracks4Africa is a really useful tool because of the information it offers,” David says. “In my job I often have to meet up with people at a set point off the beaten track and this lets me work out how to do that. I now know how long it would take to drive and I have routes that can get me there.

“Just after I’d downloaded the latest GPS maps, I did some work on black leopards in Kenya. And I discovered that other T4A travellers had actually used the route we were following. I found that quite impressive. The route was very well marked too. For example, we came to a river and there was a warning about deep water. Luckily, we weren’t there in the wet season, so we could get across.”

Travelling for work

What’s involved in getting to these far-off locations? “In Kenya I travel a lot by air – two-seater plane or helicopter – but I still use the same mapping system. We’re only a few hundred feet above the ground anyway. But aerial travel allows me to cover ground much faster. I recently did some work up in the north of the Samburu. While it was 362km to drive there, so around 5.5-6 hours, it was only 52km to fly.”

However, travelling overland is what he prefers. “I love being completely self-sufficient and when I fly I’m limited in what I can take.” Aside from his essential photographic equipment, David also takes a variety of gear so he can deal with most eventualities. That usually means a satellite phone, torch, medical kit, 2 litres of water, three protein bars, a knife… “I carry those things the whole time. I’ve been in so many situations where I get left somewhere for hours at a time, especially when working on anti-poaching projects. So I decided I need to carry enough to be self-sufficient and have the ability to know where I am.”

Finding his way

It turns out that David isn’t exactly a homing pigeon. “I’m a terrible navigator. I was doing a project on elephants in Botswana and we were on location with a community in the middle of nowhere. Yet the site was no more than a quarter mile from the road, so I decided to walk back to the vehicle to get more film. There I bumped into a member of the community and walked along with him, chatting all the while. After a while I realised he wasn’t going back to the photography site.” When the man cheerfully waved goodbye, David found himself in the middle of the bush with no idea how to get back to where he needed to be.

“I had nothing with me that could help – no Tracks4Africa, no water. I didn’t have my travel bag on me because we’d been so close to the vehicle. In the end I climbed a tree and from there I could see some other trees that I recognised. I repeated this until I spotted a telephone pole and could make my way back to the road. I must have done 10km or more in trying to find my way back. The first thing I did when I got home was to buy a Garmin watch.”

A changing world

Working on long-term photography projects has given David a unique perspective on how Africa is changing. “I’ve worked with the Samburu for more than a decade. When I started, the young men had just been circumcised and been welcomed as warriors. Now I’ve seen those same men become junior elders and there’s a new generation of warriors. I’m interested to see if in another 10 years, there will be another generation of warriors. Can the landscape support it? Or is technology now sounding such a loud call that they would rather embrace a different way of life?”

If you travel to the continent’s most out-of-the-way corners these days, you’ll find signs that the modern world can’t be shut out. Even in the most isolated communities you’ll come across sanitation stations to protect against the spread of Covid-19. David explains the genius of tippy taps, makeshift hand-washing points that use readily available materials: sticks, string, a 5L oil canister and a bar of soap. “It’s so cleverly done, you can wash your hands without touching anything.”

“Something positive that has come out of Covid is that people realise we’re all connected. In the past people may have thought of these wild places in Africa as a bit of a playground. You know, you see these amazing cultures but then you jump back on a plane and leave it all behind. Now we realise that’s not the case – when you step on a plane, you take it with you. We need to care for each other, the planet and the wildlife.”

He speaks about his time at Reteti Elephant Sanctuary again and how the time with the tiny calves touched him. “All these orphan elephants have been found in the wild. There are eight little ones, from just a few weeks to a few months in age. When you spend time with them, it’s extraordinary… you develop a bond. They come to recognise you and look to you for protection. It makes you realise how closely connected we are to them.”

Unfortunately, it may be that our instinct for understanding how we all fit together is being lost. “It’s something we shouldn’t ignore. In protecting species and preserving landscapes, we have to look at our relationship with nature – with the landscapes and the animals that live within. There’s an inter-dependency we need to protect.”

Follow photographer David Chancellor on Instagram and view a portfolio of his work.